Note from Marsha Stopa: There was a ripple in the blogging world last week when we learned that John Yeoman had passed. John ran several acclaimed fiction writing programs at his membership site Writers’ Village and was a fixture since we launched this blog. We counted on him popping into our inboxes with a wry observation, slightly cynical question or a witty comment on posts. John was a charter member of Serious Bloggers Only, fond of long, analytical and challenging debates in the forum. His clever posts were winners in every SBO blogging competition. Ever the delightful gentleman, he was widely respected for his experience, insight and willingness to help.

John sent this post to me on June 10, shortly after he became aware of his medical issues, to consider publishing within SBO. We can’t be sure, but it may be one of the last pieces he wrote. So publishing it where everyone can benefit is more fitting with the kind and generous soul that he was. He is deeply missed.

Membership sites are potentially the most profitable kind of online business.

Your product is digital, so you have no inventory or shipping costs. You can operate wherever you have computer access, even from your home (as I do). If you create your own product and do most of the techie stuff yourself, your overheads are negligible.

So your pre-tax profits might be as high as 80% of turnover.

What other kind of business can claim that?

Above all, you have to make a subscription sale only once. Subscribers on an automated payment profile will then pay you regularly, maybe across several years — provided your program is good.

Your cash flow can be excellent. And you can usually predict your income stream a year or more ahead.

So why doesn’t every blogger run a membership site in their own niche?

Because it’s not easy.

I’d guess that nine in ten subscription programs fail in year one, and the tenth is struggling. Why? Because it takes years of error to learn what works. Most bloggers (I suspect) give up.

When I started my first online program in 2012, I’d already run two highly profitable subscription businesses in the UK. One — the Marketing Guild — turned over as much as $1.4 million annually from my own front room. It was driven entirely by direct mail. (Remember postage stamps?)

Between 1986 and 2000, it grew to be the UK’s largest indie publishing business.

So I already knew what I was doing, didn’t I? Yes and no. It still took me four years of pain — starting with no technical knowledge whatsoever — to build an online subscription business that worked.

I called it the Writers’ Village Academy, a coaching program for serious fiction writers.

Want to write publishable stories or novels? The Academy will show you how. It’s intensive and advanced, with content equivalent — or superior — to that of an MFA (MA) in Creative Writing. (I know that because I once taught the MA program at a UK university.)

With more than 2000 subscribers since 2012, the program now brings me more money — on auto-pilot — than I can reasonably spend.

Like to do the same?

Ho, ’tain’t easy. (If it were, everybody would do it. And they’re not, are they?) But I’ll give you a head start.

Here are Golden Precepts that have worked for me.

Every niche and business is different, of course. But they might save you a load of pain and error, whatever niche you blog in.

Choose a niche you’re passionate about.

You’ll have to live with it a long while.

Choose a topic within the niche that you know a lot about.

You can’t just scrape info off the web untested, change the words and re-organize it. People do that, but their programs fail. Because folk can find that stuff anywhere, for free. Why should they pay you for it?

Your personal authority must be highly credible. It should shine out of every word in your program and promotions. In time, major influencers in your niche will seek you out to co-host webinars, podcasts and conferences. So you’d better know what you’re talking about.

Give your program a perceived uniqueness.

The easiest way is to brand it with your own identity. You are a niche authority, or you can credibly present yourself as one. (Don’t forget to show your photo everywhere, professionally posed. It’s your brand.)

When I launched the Academy, I already had a PhD in Creative Writing. Hardly anyone else in the world could claim that at the time. My own doctoral research had given me a special insight into how to write novels and stories that get published. My expertise was, indisputably, unique.

Two years later, I published four novels. They gained more than 100 5-star reviews across five Amazon sites in five months. Those novels added to my credentials. They proved: I walk my talk.

If you can’t — or don’t wish to — brand the program strongly under your own name or identity, organize your materials into an original formula. Give it a proprietary product name or acronym. Explain why your formula is uniquely beneficial.

You’ll need a branded product name sooner or later, in any case. Because if the program is just you (Jane Doe’s Personal Coaching), you’ll never be able to sell your business. And you’ll be forever in the loop because your subscribers will be buying you, not your service. (Kiss holidays goodbye.)

Promote a branded “product“, a self-contained formula. So people don’t buy just you. Then one day you might be able to sell your business, if you wish.

Beware of putting yourself irretrievably in the loop.

I can’t emphasize that too strongly. Some people are parasites. (Okay. It’s human nature.) They’ll squeeze you dry, and you’ll find yourself working, for your heaviest users, for $5/hour.

Create an automated system that gives subscribers the perceived benefit of one-on-one feedback (if that’s essential to your program) without you being in the loop.

My solution was a private member forum. Members critique each others’ work there, and I nod in occasionally. Obvious, in retrospect. But it took me three years to think of it. In that time, I’d been driven mad by folks who thought they’d found Santa Claus, grabbed all my goodies, mailed me a joyful testimonial, then canceled.

My system is now 95% automated. I spend my time largely on admin and troubleshooting. (“I can’t log in.”) With foresight, I could have set things up that way at the start.

Ring-fence your time from day one. That way, sanity lies.

Give proof factors, case studies, testimonials, and third-party test results.

Nobody will buy into your program without independent proof that it works. (Even an outrageous money-back guarantee won’t bail you out, all by itself. It screams desperation. And, without proof factors, how can people trust that you’ll even honor your guarantee?)

Gain early testimonials from beta testers. Enroll them in the program at no fee, and ask them to work it hard. Ideally, they should be people who have credibility in your niche, by their experience or occupation, so their names will carry weight. However, they needn’t have a web presence. Ask them for a usable but candid review of your program in their own words. A testimonial that’s too poetic in its adulation convinces nobody.

Of course, be sure to ask your beta testers to alert you to errors, dead links, misspellings and other problems in your program.

Make it very easy for people to join your program on a rolling subscription.

Let people test it for no charge for a trial period of, say, four weeks. Or for a token fee, refundable when they pay their first real sub. But make sure they’ve set up a valid payment profile, direct debit mandate, or the equivalent, before you send them anything significant.

Incidentally, it’s often worth asking people to pay a token fee up-front — e.g. $3 (refundable or not). It’s a qualifier. If they pay it, they’re serious. It also deters those with dodgy credit cards, or no money in their PayPal account, or who never intended to continue with you anyway.

When you launch the program, price it low — initially.

Your first task is to build a viable member base and gain testimonials and referrals. Don’t be greedy. Remember, you plan to run this business across a long period. (Don’t you?)

You can — and should — increase the price later, when you can point to 1,477 satisfied members, or the like.

Beware of “giving it all away” with a price that’s permanently low.

Plan to at least double your price within, say, six months. The higher your price (within reason), the fewer time wasters you’ll get — and the greater your overall revenue.

The downside is… people in the consumer market are paying out of their own pockets. If your price is very high, they’ll demand your soul in return. (It’s different in the corporate market where you have to quote a high fee to gain any credibility. How do I know? Thirty years ago, I ran a blue-chip PR consultancy.)

Incidentally, when you increase your price, leave your existing subscribers alone. Let them continue at their original fee. If you ask them to sign a new mandate at a higher price, they’ll cancel. And rightly so. Aren’t they due a special rate for life as your cherished Charter Members?

Be prepared for a few “problem” subscribers.

They’re the ones who forgot that they’d signed up. Or who never read your terms of service (even though they’re set in 18 point type right beside your Subscribe button). Or who are simply mad. They’ll whine when their first subscription hits. Maybe they’ll raise a PayPal or credit card dispute.

If your business is ethically run, problem subscribers should account for less than 1% of your member base. But a few cranks can make your life hell.

Refund them at once. Don’t challenge them, even when they’re wrong. PayPal and the credit card companies will always find in favor of the customer, regardless of the merits of any case. It isn’t worth the risk of seeing your PayPal account limited while you contest a claim over a few dollars.

Email them a message of exquisite courtesy. Apologize and make them right (especially when they’re wrong). Decent people will have an attack of conscience and send you an apology of their own. Many times, I’ve seen a crabby customer — handled well — turn into a friend, and stay with me for years.

Present your course materials at regular intervals, ideally weekly or every two weeks.

(A monthly schedule lacks impetus.) I’ve found the easiest way is to put each module on a dedicated page on my website, each with its own cryptic URL.

Why cryptic? That way, rogues can’t work out that module #1 is named “[site url]/plotting1,” therefore subsequent modules must be named “[site url]/plotting2/3/4,” etc. And so gain my entire year’s program without further charge.

Password protect those pages so Google spiders can’t pillage your hard work and splatter it across the web for the world to access.

Find a payment portal that lets you create subscription profiles for members, in a flexible way.

I use PayPal, although I (and plenty of my members) dislike it. No other payment portal, to my knowledge, lets you define a free — or token cost — trial period for new subscribers. Or pause, then re-activate, a member’s payment profile at their request.

You need that flexibility. PayPal’s quirks, often maddening, are a small price to pay for it.

A monthly payment schedule is about right. Charge subscribers every week and you’re goading them — every week — to ask, “Do I really need this service?” Hit them with a large sum every quarter (or year) and they’ll certainly ask themselves that question.

Set up an email program (say, at AWeber or MailChimp) so subscribers get an email in an automated follow up sequence every few days.

Each email gives a link to the next module.

A friend wrecked his business when he tried that. He set the system up wrong and found that AWeber (or it might have been MailChimp) had somehow canceled all his members’ PayPal profiles. Once a PayPal profile has been canceled (as opposed to suspended), you can’t re-activate it.

When the formal part of your program ends (after 12 weeks, 13 months, or whatever), encourage subscribers to carry on paying you regardless.

Call them alumni. They’ll still gain access to you — or a simulation of you — or aspects of your service. Amazingly, many members will stay with you, out of inertia or genuine loyalty, indefinitely.

Consider whether your entire subscription program could be delivered by email follow-ups alone.

It’s possible, if your materials are pithy. I did it successfully with Story PenPal, a highly simplified, low-budget version of the Academy. It presents story ideas every week — no more than 1000 words per email — with a link to a user forum.

However, an email by itself lacks flexibility. Attach a file and spam filters may block your email. You don’t have room — in an email alone — to expand upon a topic or present complex materials and graphics. (People also tend to mislay emails.)

With a link to a dedicated web page, you have no space limitations, and you can regularly update your content. (I’ve updated every one of the 64 weekly modules in my Academy series several times across four years.)

Expect a 50% cancellation rate during any free trial period.

Don’t take it personally. Many people will join on impulse, having no motivation or means to pay. After some 4-5 months, the cancellation rate abates as people grow loyal to your program.

I promised subscribers a 30-day “cooling off” period before I processed their mandate. Indeed, I urged them — for their peace of mind — to date the mandate 30 days ahead.

When they became full members — i.e. I’d processed their mandate — they got a big printed newsletter every month plus free entry to all my future conferences, for themselves and their guests. (I encouraged them to bring business guests for free. They were my best source of future members!)

Meanwhile, I mailed new subscribers a big box of materials, at my own expense. They could keep it whether they canceled or not. This was the thud factor. It mitigated post-purchase remorse. It made their subscription real.

Exactly 50% of people would cancel within 30 days.

That meant 16% of the room stayed with me, and many stayed a long time.

Across 15 years, and 52,000 delegates, those ratios never varied. So I could budget to lose as much as $5000 per workshop on marketing and hotel costs, certain that I’d get it back within a few months and make a good profit in year two.

Moral: learn your ratios and trust them.

Of course, I needed a lot of capital to keep funding my promotions and hotel rooms. (At one time, I was throwing the equivalent of $50,000 into direct mail every month.) Luckily, I had the money. Subscription programs — where people pay ahead — are cash rich by their nature.

However, you don’t have those up-front costs with an online program, delivering a product or service digitally. So you need little cash to keep it running.

Cancellations? If the program costs you little or no money to deliver, they don’t matter. Provided a healthy number of subscribers stay.

But beware (as I’ve said) of giving anything of value — especially your own time — until people have paid you at least one subscription.

For example, members who join the Academy on a four-week free trial don’t get access to our private Forum until week five, after they have paid their first subscription.

Prepare to top up the membership base continually.

Churn is inevitable in membership sites. I top up my member base two ways:

1. When people join my free mailing list, they get a no-charge 14-part mini course in fiction writing, delivered every two days.

Clever, original ideas of high quality. (An intense schedule is important at this stage to hold people’s interest while it’s warm. Run a more relaxed follow-up schedule and people will have forgotten who you are by week two.)

Every second module contains a small clickable ad for my paid-for Academy program, and some people do join that way.

Halfway through the mini course sequence, and at the end, they get a hard sell. That also works.

If they still haven’t joined the Academy, they revert to my general mailing list and receive emails every week, alerting them to my latest blog posts. I run the posts to build a relationship with my followers. The posts also bring traffic to my site and list via organic (keyword) search.

2. Every 6-8 weeks, I hit my entire list with a hard sell.

But I test each hard sell message first on small list segments.

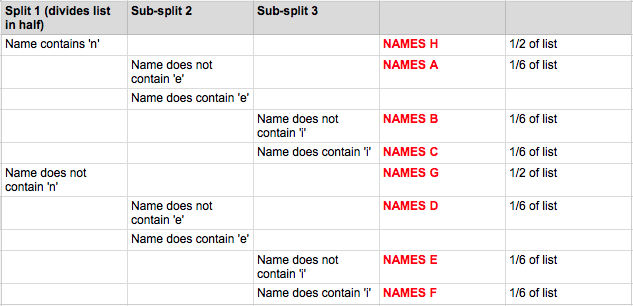

So I devised my own algorithm. It splits my list roughly into equal-sized segments so I can tell exactly which names have received which offer.

Note: these splits only work with a fair-sized list of, say, 4000 names or more. Trying to split test just a few hundred names this way will yield meaningless results.

Some hard sells (usually my cleverest ones) flop. If one works, I roll it out to the entire list. But it’s important not to “burn” a list with too many hard sells. People just tune them out or unsubscribe. A reasonable ratio, I find, is one hard sell per 5-6 emails having beneficial (non-sales) content.

I could easily automate my tested hard sell emails and schedule them — at 6-8 week intervals — a year or two in advance. Given the subscribers who drift into the Academy by themselves, from the ads in the follow-up sequence on my general list, I wouldn’t have to pay any further attention to sales promotion whatsoever.

I’d have a totally automated money machine. (Admin apart.)

List Building

The list is the foundation of a membership site. At the Marketing Guild, I rented my lists in as many as 100,000 names at a time. But the list rental rules have since been tightened up. Although you can still rent or buy email lists, they’re likely to be dross and/or illegally acquired. Ethical email services like AWeber, MailChimp, etc. won’t let you use them. And rightly so.

I’ve built my list across seven years (the Writers’ Village site has operated since 2009) to become one of the largest in my niche. I try to keep it scrupulously clean. Every three months I delete those who haven’t opened my emails for six months plus those living in countries who have no PayPal access. (Why pay to host people who can’t pay me?)

Each name on my list is notionally worth £5 (around $8). That benchmark is important when I’m advertising for sign-ups. A name must cost no more than £1 to acquire, to cover its hosting costs across a long period and still yield a profit if and when it converts to a sale.

I’ve gained names in three ways:

1. Guest posting at other people’s sites.

In 2014, I published around 80 guest posts across 30 writing sites. I found only one site that reliably brought me 60-80 sign-ups per post, plus a few that averaged 15-20. (Others yielded just a handful of sign-ups, although the quality of the posts was much the same.

Each post took me two days to write/edit, so the notional yield from my best site was £300-£400 per post. That was an acceptable yield but hardly wonderful.

Lower performing sites were a total waste of time.

Now I guest post only by request and for fun. I don’t need guest posts any longer to build my list.

2. Advertising.

After testing many sites, forums and ezines (newsletters), I found only two that gave me a worthwhile ROI. And I had to rest those vehicles for several months before I could advertise again. Too many ads, too often, brought diminishing returns.

Banner ads on sites and forums have never worked. Nor could they work, on reflection. The math is against it.

Why? The average click-through rate for banner ads is just three-tenths of one percent or 0.3%. That’s the industry average according to imediaconnections.com.

So only three in 1000 people who see your banner ad will click on it. Even if 40% of those people join your list (a common sign-up ratio), you’ve acquired just one name. How much will you be charged for that banner? Anything between $100 and $1000.

Even worse — if it can get any worse — are rotating banner ads. (Now you see them, now you don’t.) They appeal only to kiddies who like duck shoots.

Google and Bing ads proved a total waste of money. That said, I didn’t have the patience to play games with longtail keywords, click bids and SEO. If I’d had the mind for such voodoo, I’d have been a hedge fund manager.

Facebook ads? They come well reported, especially since FB changed its advertising procedures so you can now target people in complex ways by their affinities rather than, simplistically, by their interests. But like Google ads, Facebook ads are a steep learning curve. I wish you luck.

Twitter ads? Never tried them, or wanted to. I’ve always felt that the kind of people who hang out on Twitter — except for commercial purposes — are unlikely to have enough IQ points to join my program. (Okay, call me snotty.)

3. Organic search.

Most of my sign ups now come from magpies — my name for people who flutter into my site following keyword searches at Google, Bing and the like. Hence, the importance of having a lot of archived blog posts at my site. (I now have nearly 200.)

Every post has a prominent sign-up box above it. Every high-traffic page has one too. And the sign-up box is always at the top of the page.

What about boxes that pop up or slide in or flash? I’ve never tested them. But I have wondered about the quality of the names captured that way. “Alright, already!” I hear people cry. “I’ll sign up just to get rid of your stupid box!”

Qualified names? I think not.

It’s amazing how many magpies discover my hidden posts that go back several years by following keyword searches. Hence, the importance of putting keywords in your post titles. (My all-time winner has been ‘How To Create A Brilliant Detective.’ Don’t ask me why.)

How do you write those posts? I refer you with great respect to SBO and Jon Morrow. Follow his advice and you won’t go wrong.

Pinterest also brings me a lot of sign ups, though I can’t easily track their conversion to sale. So I’ve found it important to pin the main illustrations in each of my posts to Pinterest.

Magpies are wonderful things. When you reach the point when you don’t have to promote your site to get traffic, but you can rely on magpies alone to top up your list, you’ll know you’ve arrived.

Other sources of names #1: Social networking.

I promote all my weekly blog posts at Facebook, Twitter (via Triberr.com) and Google +. However, clickthroughs from these sources are sparse — although Triberr is supposed to give my posts a reach of millions via the tweets of fellow Triberr members and I have a respectable 4,700 Google+ followers.

Maybe I don’t understand social networking? (Frankly, the more I look at it, the less I want to.) I’ve seen desperate bloggers try to penetrate the noise by posting as many as 100 messages a day on FB, Twitter and Google+, using automated systems. Splat! Does the Internet need even more noise? I don’t.

That said, I have gotten around a dozen sign-ups to my free mini-course whenever I’ve posted a hard sell at Google+. But I don’t do that more than once a month. Call it self-respect.

Stumbleupon? I tried it a few times. Didn’t work. Gave up. Ditto, Medium.com. Ditto, Hubpages.

Other sources of names #2: Joint Ventures

Once you have a good market reputation, a tested product and (optionally) a big list, you can explore joint ventures (JVs) with other site owners in your niche.

I’ve had excellent results when promoting somebody else’s non-competing program to my list, and, in return, they’ve promoted my program to their list.

No money changes hands. There’s no risk. Results on both sides are easily tracked. If both your lists are of the same size and quality — and you can trust each other to play fair — it’s a win-win.

Highly recommended.

I’m less sure about complex deals that involve a site owner promoting one’s program to their list in return for a financial commission. I ran two such JVs. They were profitable but, in retrospect, not worth the hassle.

Such deals are simple to set up if you sell a digital product for a one-time payment. Subscription services are more problematic — for example, how do you agree on a commission? I gave my JV partner the first month’s commission from every subscriber gained from their list who stayed with me past the free trial period.

That worked. But it was difficult to administer. Software programs exist that can automate JV commissions, but they’re not worth exploring until your list is vast.

Affiliate programs. Never tried them. Never wanted to.

Conclusion

Using the techniques above, I have now built a money machine that yields me a six-figure annual income, and 95% of it looks after itself. But it took me four years of pain and error.

If I were to start again, I’d invest my time in a massive program of guest posting. I’d also run low-cost text ads, testing as I went, in selected newsletters in my niche.

As my list grew, I’d phase out the guest posts, continue with the ads and make sure I ran a great post on my blog every week — to keep my list happy and bring in magpies via organic search.

Could I do it all again — in, say, two years — starting from scratch? Perhaps. And maybe you could too. But with three provisos:

- Your program must be good. It should meet a genuine market need. And be a great value for money. (So it brings you few complaints or refund requests.)

- You run it totally ethically from day one. Shortcuts don’t work. The real profits lie in the after-market — the revenues that roll in from happy subscribers year after year after year. Only ethical businesses survive beyond their first year.

- You love what you’re doing. Otherwise, you’ll burn out.

Good luck!

from

http://redirect.viglink.com?u=https%3A%2F%2Fsmartblogger.com%2Fmembership-site%2F&key=ddaed8f51db7bb1330a6f6de768a69b8

No comments:

Post a Comment