You want people to read your content, right?

That’s why you wrote it in the first place.

But getting people to read your content in today’s world of speedy news, food, and pleasure is a challenge. You’re not just competing with other writers, but with everything online — cat videos, Kardashian gossip, Game of Thrones, etc.

With all the available alternatives, your readers are easily distracted.

Most people who land on your page will scan it and decide, within seconds, to either leave or stay.

And one of the biggest turn-offs for online readers is poor paragraph structure.

That’s why you must master the art of writing paragraphs for today’s audience, and the first step to do so is to forget everything you learned about it in grade school.

Let me explain …

Why You Must Forget Everything School Taught You About Writing Paragraphs

The paragraph was born from a desire to topically organize long blocks of text. And for a long time, that worked.

“When the topic changes,” your grade school teacher said, “so does the paragraph.”

While that practice still mostly applies to print media — books, magazines, and sometimes newspapers — it’s an outdated rule of thumb for the larger rally of writers who spend the bulk of their time publishing online content.

Consider the drastic difference in paragraph length between this teacher-pleasing page from Habits of a Happy Brain and this online article by Tomas Laurinaricius that reviews the same book.

The difference in paragraph structure is obvious.

But why has the paragraph changed?

The main reason for the paragraph’s evolution is the way we consume media. Print publication is no longer top dog; online publication has become the primary media for consuming written content.

We read more from our screens than from the page, which completely changes how we approach the act of reading.

When we open a book or magazine, we’re usually at home or somewhere quiet and giving it our full attention. We usually set aside some time to dive into a book or magazine.

Online, a multitude of ads and pop-up notifications threaten that undying attention, especially when we’re reading on our mobiles.

The reading habits of our audience have changed, and we must change with them or risk being ignored.

So here are the rules for writing paragraphs that will be published online. Use them to your advantage the next time you sit down to create.

The Rules of the 2017 Paragraph

Rule #1. Short Paragraphs Are Mandatory

One of the best ways to instantly turn off your audience is to present them with a big wall of text that has few breaks and little white space. A visitor who looks at such a page will click the back button faster than you can cry, “Please give it a chance!”

We have adapted to expect and prefer paragraphs that are short because they look and feel easier to read. Short paragraphs are easier to scan, and they allow readers to consume the article in bite-sized chunks, which helps maintain their focus — and this is critical in this age of distraction.

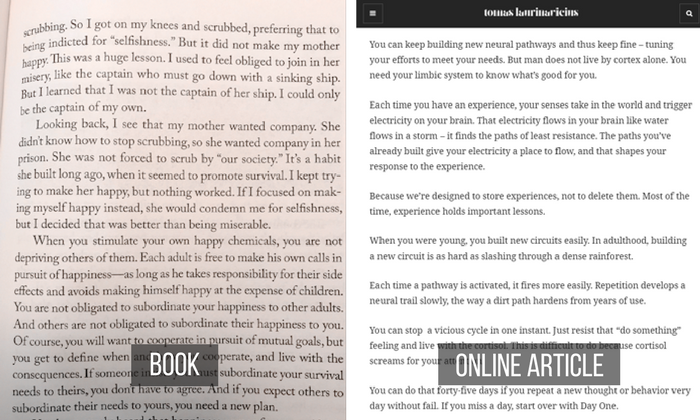

Consider, for example, the ease with which you can read the introduction to this article by Mel Wicks.

Yes, Mel Wicks uses empathetic language and easy-to-read prose, which no doubt enhances her clarity. But you can’t ignore the sense you get just by glancing at her article that it will be an easy read.

This is the effect that short paragraphs have on readers.

In her above article, there are ten paragraphs. The longest paragraph is 42 words, and seven of them have only 12 words or less.

The 100- to 200-word paragraph standard is crippling before our eyes.

So what’s the new standard? How short do you have to be?

Well, your average paragraph should be between two and four lines. You can go over and under — some paragraphs are just one word long — but stay close to that average and you should be fine.

Rule #2. Rhythm Dictates the Next Paragraph

Rhythm is the new arbiter of words. It determines where paragraphs end and where new ones begin.

Rhythm in writing is something that’s hard to teach. It’s not an exact science and doesn’t follow hard rules. It’s something that you mostly have to feel out.

The more experienced you become as a writer, the more you’ll develop your rhythm. But in the meantime, you can follow these basic guidelines:

1. Variation

As mentioned earlier, you want to keep your paragraphs short, but that doesn’t mean every paragraph has to be under 50 words. In fact, switching between short and long paragraphs will make your writing sing.

Here are a few noteworthy rules of thumb. You don’t have to follow these perfectly, but they’re worth remembering.

- If you just wrote one or two paragraphs that are four lines or more, shorten the next few paragraphs.

- If you just wrote one or two paragraphs that are only one line, lengthen your next few paragraphs.

- If you just wrote three to four paragraphs of similar length, shorten or lengthen your next paragraph.

Too many same-sized paragraphs in a row will bore your reader. It doesn’t matter if it’s too many small paragraphs or too many long paragraphs, the effect is similar.

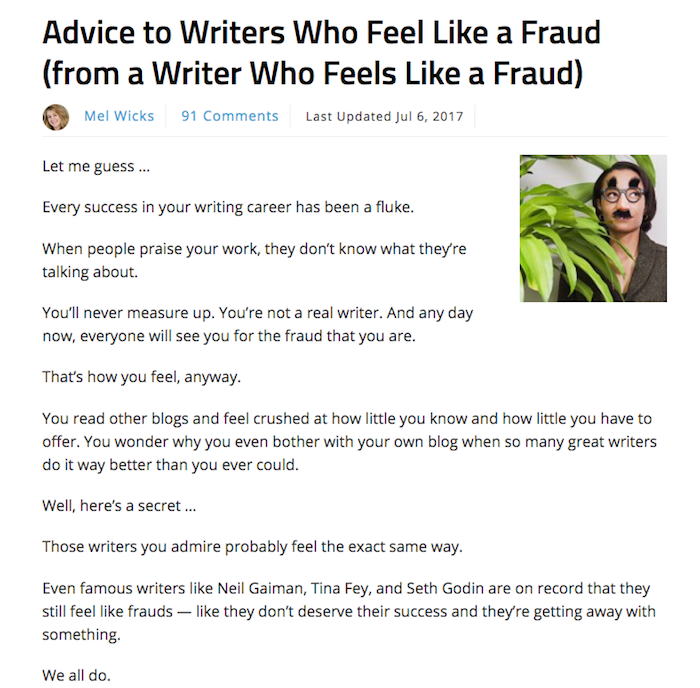

Consider this excerpt from Jon Morrow’s post on earning passive income online:

See how he perfectly balances between short and long paragraphs?

Now imagine if the same excerpt were structured this way:

The reason I put “passive income” in quotes is I think the term is a little misleading.

Almost nothing is totally passive.

While you may not personally be doing any work to receive the money, someone is.

And there’s usually at least a little bit of management overhead.

For instance, I’ve gone on record saying this blog averages over $100,000 per month.

From that total, about $60,000 of it is technically “passive income.”

Because I don’t have to do anything to generate it.

I could die, and the money would keep coming in month after month for years into the future.

But that doesn’t mean no one is working.

It also doesn’t mean I’m personally receiving the entire $60,000.

The truth is, most of that money goes to paying my team.

Even though all of these paragraphs are short, this text feels monotonous. Too many short paragraphs make a reader feel like they’re on a rollercoaster ride with no destination — they’re moving fast but they quickly get confused about where they’re going.

Similarly bothersome is if the excerpt were structured this way:

The reason I put “passive income” in quotes is I think the term is a little misleading. Almost nothing is totally passive. While you may not personally be doing any work to receive the money, someone is, and there’s usually at least a little bit of management overhead. For instance, I’ve gone on record saying this blog averages over $100,000 per month from selling online courses.

From that total, about $60,000 of it is technically “passive income” because I don’t have to do anything to generate it. I could die, and the money would keep coming in month after month for years into the future. But that doesn’t mean no one is working. It also doesn’t mean I’m personally receiving the entire $60,000.

The truth is, most of that money goes to paying my team. We have course instructors, customer support representatives, marketing specialists, and so on. All of them are working full-time to keep the “passive income” machine running, and they do it quite well. But somebody still has to be the boss.

While I don’t technically do any of the work necessary to generate that income, I do spend about 10 hours every week on phone calls and meetings. I also spend at least another 10-20 hours a week thinking about how to improve the business and make things run more efficiently. So, in reality, I’m working 20-30 hours per week for the “passive income.” In exchange, I receive a nice salary, plus the majority of the profits the business generates.

Visually, this looks dull (and somewhat daunting) to read, and a casual reader is likely to be turned off by it.

In the original, however, each paragraph is appropriately varied, which doesn’t just look but also feels pleasant to read.

Ultimately, you want to guide your reader. And the only way to do that effectively is to recognize when your reader needs a few short paragraphs, a long one, or a bit of both.

2. Topic

While topic was once the ultimate indicator of paragraph change, it is now one of many. Topic is still critical for clarity. If you change paragraphs at a topically awkward time, the split disturbs the reader.

Take, for example, this excerpt from Liz Longacre’s article:

Blogging is a battle.

A war to get your ideas the attention they deserve.

Your enemy? The dizzying array of online distractions that devour your readers.

This battle is not for the faint of heart.

There are so many learning curves. Plugins you’ll need to install. Social networks you’ll need to employ. Marketing techniques you’ll need to try.

Imagine these paragraphs were structured like this instead …

Blogging is a battle.

A war to get your ideas the attention they deserve.

Your enemy? The dizzying array of online distractions that devour your readers.

This battle is not for the faint of heart. There are so many learning curves.

Plugins you’ll need to install. Social networks you’ll need to employ. Marketing techniques you’ll need to try.

Notice the difference in how you read the original paragraph versus the variation.

In the original, the last paragraph tactfully emphasizes the difficulty of learning how to blog. But in the variation, you take a mental pause between “There are so many learning curves” and “Plugins you’ll need to install.”

And it feels off, doesn’t it?

The last three sentences are examples of learning curves, which means they are topically linked to the phrase introducing them.

It reads even worse as follows:

This battle is not for the faint of heart.

There are so many learning curves. Plugins you’ll need to install.

Social networks you’ll need to employ. Marketing techniques you’ll need to try.

See what I mean?

Due to our topically-paragraphed past, readers still expect that topics will — for the most part — stick with each other. It still reads better that way.

Just avoid beating topics to death. Allow topics to change as they need to — which should be every few sentences.

3. Emphasis

Paragraphs of one short sentence naturally add emphasis.

This can be used to highlight ideas you want the reader to take note of, but it can also be used for dramatic effect.

For example, check my introduction to an article for Carrot — a SaaS company that caters to real estate investors.

See how the introduction guides the reader through the feelings they experience regarding content marketing with a long paragraph, and then emphasizes, “So you quit producing”?

This phase conveys a dramatic turn of events. The shortness of the paragraph emphasizes this.

The longer paragraph that precedes this phrase preps the reader for the punch. The effect wouldn’t be quite the same if it was preceded by a paragraph that was similarly short.

But you don’t always have to go from a long paragraph straight to a short paragraph to create emphasis. You can also use a gradual decline in word count and finish with your main point. This builds the reader up to the punchline.

Here’s another example, taken from The Brutally Honest Guide To Being Brutally Honest. The author, Josh Tucker, decreases wordcount over three relatively short paragraphs to bring attention to his final sentence: “How you end the discussion can make all the difference.”

Think of paragraph length in the same way you think about the rest of your writing. Your word choice, sentence length and paragraph structure all have a massive impact on what your article communicates.

Ultimately, paragraph emphasis is up to the creativity of the writer. Paragraph length is simply another tool at your disposal.

Write Paragraphs for Today’s World and Readers Will Thank You

Yes, you want people to read your content.

And despite the difficulty in grabbing the attention of today’s readers, you can still turn visitors into content absorbers by crafting easy-to-read paragraphs — paragraphs that are short, rhythmic and varied.

Doing so is simply a matter of being aware of the way your paragraphs are structured. Once you’ve mastered the art of the paragraph, you’ll do much better at keeping your readers’ attention. People will crave your content and they’ll look forward to the next time you publish.

They’ll appreciate your courteous writing and — dare I say? — they’ll keep coming back for more.

from

https://smartblogger.com/how-to-write-a-paragraph/

No comments:

Post a Comment